Selecting an isolating valve for a potable water pipeline isn’t just a line-item purchase, it’s a long-term investment in reliability, safety, and operating cost. With so many valve types positioned as “fit-for-all,” engineers need application-specific guidance grounded in hydraulics, maintainability, and lifecycle value.

This guide simplifies the decision by mapping common potable-water functions to the isolating valves that perform best in each role, plus what to avoid and why.

Quick reference: which valve where?

| Pipeline function | Best choice | When to use | Acceptable alternatives | Avoid / Caution |

| Pump suction isolation | Rising spindle wedge gate valve | Full-bore, low turbulence, visual position | Non-rising spindle gate valve (space-constrained, with position indicator) | Butterfly valves (disc disturbs inflow/NPSH; if unavoidable, extend straight length) |

| Pump discharge isolator | Resilient-seated gate valve (≤PN16, ≤DN250–300); Metal-seated wedge gate (>PN16 or >DN250) | Started against closed valve; installed after the check valve | Butterfly valve (large bores) subject to pressure, distance from pump & NRV | Underspecified RSVs at high pressure/large bore |

| In-line pipeline isolation | RSV (≤300NB, ≤PN16); Wedge gate (frequent pigging) | Low headloss, piggable | Butterfly valve (large diameter, low head/low flow) | Selecting solely on unit price without checking pigging, pressure class |

| Scour / line end isolation | Metal-seated wedge gate | Durable under high velocity/pressure; rodent-resistant | RSV only if protected | RSVs left dry (rubber degrades/rodents damage); if used, fit Flap Gate at outlet |

| Air valve isolator | RSV (low pressure); Wedge gate (high pressure) | Maintains air path and reliability | Full-bore 316SS ball valve with RPTFE seats (¼-turn) | Butterfly valve (turbulence/restricted air flow) |

Pump suction isolation valves

Smooth inflow at the pump eye is non-negotiable for NPSH and efficiency.

- Recommended: Rising spindle wedge gate valve (full-bore, low turbulence). The exposed stem gives clear open/closed confirmation, vital for safe starts.

- Alternative: Non-rising spindle gate (space-saving). Add a mechanical position indicator to avoid mis-starts.

- Avoid: Butterfly valves at suction. Their disc obstructs the approach flow and erodes NPSH margin. If a butterfly is unavoidable, increase the upstream straight length to 10D (vs. 6–7D for gates) and confirm NPSH available > NPSH required with margin.

Design tip: Provide a minimum 6–7D straight run into the pump for gates; verify strainers, reducers, and elbows don’t intrude on this approach.

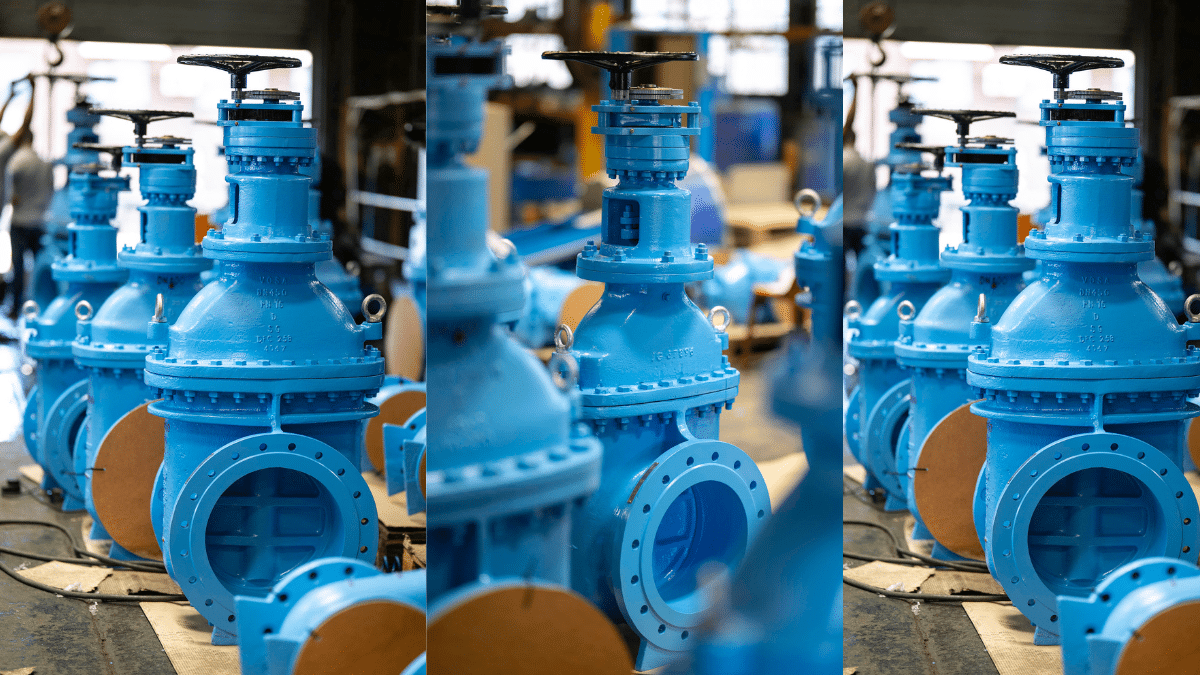

Pump discharge isolators

Most centrifugal pumps start against a closed valve and open gradually.

- Low pressure / small diameter (≤PN16, ≤DN250–300): Resilient-seated gate valves (RSVs) offer tight shut-off with low headloss.

- High pressure / large bore (>PN16 and/or >DN250): Metal-seated wedge gate valves handle higher ΔP, temperature swing, and mechanical loads.

- Alternative: Butterfly valves are common in large diameters for cost/weight advantages, but selection must consider:

- Distance from pump and non-return valve (NRV),

- Operating pressure and transients, and

- Required flow characteristics and maintenance access.

Layout best practice: Place the isolator downstream of the check valve (NRV) to enable safe removal and servicing of the check valve.

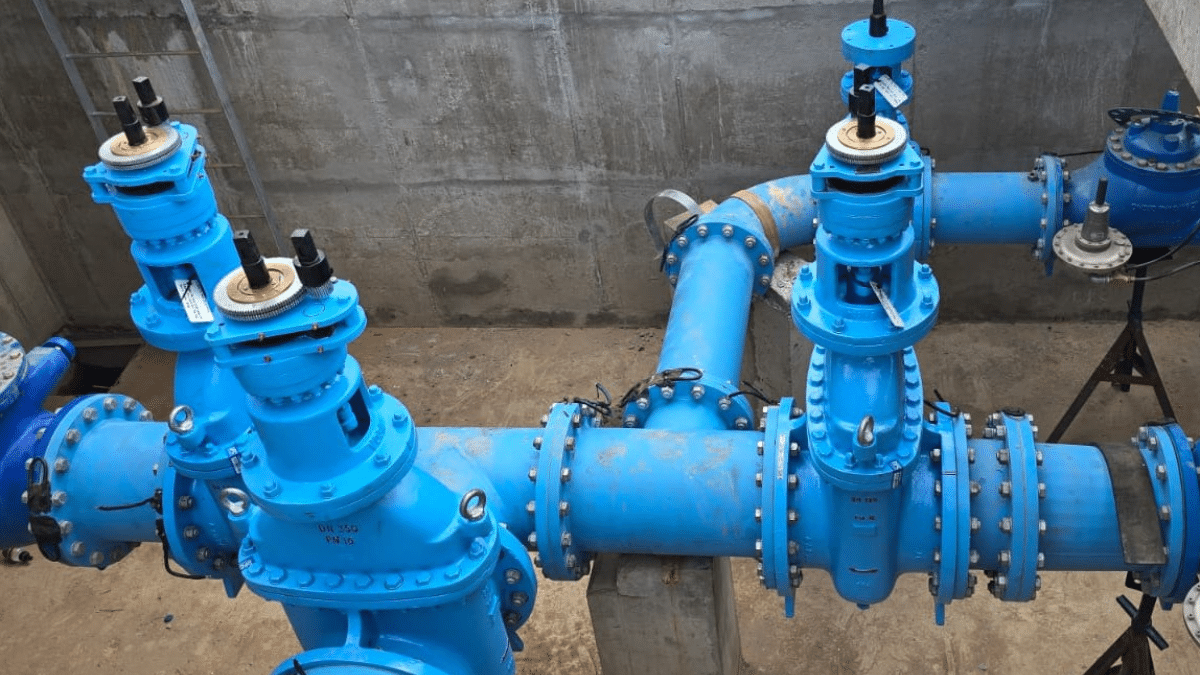

Pipeline isolation along the length

Valve choice is driven by diameter, pressure class, pigging, and budget.

- Small diameter, low pressure (≤300NB, ≤PN16): RSVs give reliable shut-off at low cost.

- Large diameter lines:

- Butterfly valves suit low head / low flow applications where the line isn’t routinely pigged.

- Wedge gate valves where piggability is essential (full-bore path, no shaft or disc intrusion).

Network operations tip: Standardise on a small number of valve interfaces (flange drilling, operator gearboxes, extension spindles) to simplify spares and crews.

Scour valves / line end valves

Scour points see high velocities, intermittent use, and exposure to the environment.

- Best choice: Metal-seated wedge gate valves, robust, tolerant of solids, and not vulnerable to rodents or UV.

- Not recommended: RSVs left dry for long periods, rubber can degrade or be chewed.

If RSVs are used for budget reasons, install a Flap Gate at the scour outlet: it protects the valve, keeps wildlife/children out of exposed pipe ends (common near rural villages), and limits ingress.

Air valve isolators

Maintaining an unrestricted air path is the priority.

- Low pressure: RSVs are cost-effective and adequate.

- High pressure: Prefer wedge gate valves for reliability and minimal turbulence.

Avoid butterfly valves here—disc obstruction reduces air throughput and can cause chatter. - Third option: Full-bore 316SS ball valves with RPTFE seats; the ¼-turn action is fast and the bore stays clear.

What isolating valves are not for

Isolating valves are on/off devices, not control valves.

Don’t throttle with them and don’t subject them to high-cycle open/close duty. Use dedicated control valves for modulation.

Lifecycle and total cost of ownership (TCO)

While RSVs and butterfly valves are heavily marketed, their initial price advantage often fades in service.

- Typical lifecycles (with correct duty & maintenance):

- RSV: ~10–12 years

- Wedge gate valve: ~25–40 years

- Why the gap? Seating materials, stem/drive robustness, tolerance of pressure transients, and sealing integrity under debris or misalignment all influence service life.

Example TCO snapshot (illustrative)

- DN300, PN16 line isolation over 30 years:

- Option A – RSV

- Purchase: R1 (baseline)

- Replacements: once a year ~12 and ~24 → 2 extra purchases

- Planned maintenance + parts (glands/liners/fasteners): ~0.6R

- Indicative TCO ≈ 3.6R

- Option B – Wedge gate

- Purchase: 1.6R

- Replacements: 0 (over 30 years typical)

- Planned maintenance + parts: ~0.4R

- Indicative TCO ≈ 2.0R

- Option A – RSV

Even with a higher upfront cost, the wedge gate delivers lower 30-year spend and fewer shutdowns.

Installation & specification checklist

Use this pre-commissioning checklist to de-risk selection and layout:

- Hydraulics

- Suction straight length: 6–7D (gates) or 10D (if butterfly unavoidable).

- Confirm NPSH(A) – NPSH(R) margin at worst case (hot water, low level).

- Transient analysis for discharge and long lines; specify gearboxes or slow-open actuators as needed.

- Function & duty

- On/off only; no throttling requirement.

- Cycle frequency within manufacturer limits.

- Maintainability

- Clear visual position (rising stem or indicator).

- Isolator after NRV on pump discharge.

- Spindles/gearboxes accessible; stems protected where exposed.

- Compatibility

- Bore and seat suitable for pigging (if required).

- Pressure class (PN) and materials matched to water quality and external environment.

- Scour & air lines

- Scour: choose metal-seated gates; add Flap Gate at outlets.

- Air isolators: avoid butterfly; prefer RSV (LP) or wedge gate (HP), or full-bore SS ball.

- Lifecycle

- Budget for maintenance and realistic replacement intervals.

- Stock common spares (O-rings, packing, indicators).

Common pitfalls to avoid

- Putting a butterfly valve on pump suction and losing NPSH margin.

- Selecting RSVs for dry, exposed scours without Flap Gate protection.

- Forgetting pigging requirements and installing non-full-bore valves in sections that must be piggable.

- Using isolators for throttling, causing premature seat wear and leakage.

- No position indication on non-rising spindles, leading to start-up errors.

Also Check: RGXII Air Valves: Siza Water Infrastructure Management

FAQ

Q: Are butterfly valves ever acceptable on potable water systems?

A: Yes, particularly on large diameter pipelines with low head/low flow where pigging isn’t needed. Avoid them on pump suctions and air valve isolators.

Q: When should I choose a metal-seated gate over an RSV?

A: At higher pressures (>PN16), larger diameters (>DN250–300), scour points, or where high velocities, debris, or temperature swings are expected.

Q: Do I need gearboxes or actuators?

A: For large diameters, high differential pressures, or where controlled opening speed is critical (transient control), gearboxes/actuators improve safety and repeatability.

Choose isolators for what they are: on/off devices. In potable water duty, wedge gate valves consistently deliver the best long-term reliability across demanding applications, while RSVs are economical for smaller, lower-pressure lines; provided they’re used where they excel. Butterfly valves have a place in large, low-head lines; but keep them off pump suctions and air isolators.

When you weigh total lifecycle cost, including maintenance and replacement, the apparent savings from the cheapest option often disappear.

Need help matching a valve to your duty?

Talk to a DFC valve specialist for a duty-matched specification and lifecycle estimate.